Yes on I-135

Why am I voting YES on I-135?

I’m voting YES on Initiative 135 (I-135), the special ballot measure to be decided on February 14 that would create a social housing developer in Seattle. Why? Because social housing is a proven strategy to guarantee affordable housing supply, and I believe that this housing would be equitable, sustainable, and desirable.

It was difficult to come to this conclusion because it’s a new idea in the US and I had to do some research and vetting of popular opinions. I also think that it’s being unfairly judged as a replacement for existing solutions, rather than a new and complementary solution to the work that we’re already doing. For example, I thought there were a number of misleading statements made in the Seattle Times “no” endorsement.

In this post I’ll clarify what confused me in that opinion and in doing so hope to further illustrate the kinds of communities that social housing can create. If we want to create these communities, then we need to start investing in them now by passing I-135.

What is social housing?

To paraphrase the I-135 FAQ: Social housing is housing created outside of the private market, publicly financed and publicly controlled. Residents and their homes are shielded from the free market, with specific measures prohibiting the sale and marketization of social housing to ensure it remains in the public’s hands for public use.

How can we pay for social housing?

In its “no” endorsement of I-135, the Times editorial board begins:

“There is no price tag because funding is uncertain. Its business model is unrealistic”

The first statement is true. There is no price tag in the ballot measure because the ballot measure only creates the Seattle Social Housing Developer (SSHD), which is a Public Development Authority (PDA) similar to the ones that administer Pike Place Market and Chinatown-International District. However, the business model is proven and has been operational for years in Montgomery County, Maryland. Understanding how Maryland’s Housing Opportunities Commission (HOC) creates a public housing portfolio in the Housing Production Fund (HPF) shows how the Seattle program could be funded:

- The County gives HOC $3 million per year. This is a grant.

- HOC issues a bond on that revenue stream from the county and gets big wad of cash that they put into the Housing Production Fund. This is debt.

- HOC combines funds from the HPF with conventional debt and outside equity investment to fully fund and then build the project.

- After the project reaches stabilization (at four years) HOC issues another bond on the revenue stream of the rents being collected to buy out the HPF investment. Other investors have the option of being bought out or converting their equity to subordinate debt—meaning that HOC takes 100% ownership of the project, and bought-out funds are invested back into the HPF so HOC can do it all over again.

(from Paul Williams)

Similar to the HOC, the SSHD would have bonding authority so that it, too, could use a relatively small amount of public funding to raise enough debt capital (via bonds) to complete new social housing developments, and then pay back the bonds over time. Once the bonds are paid out, all future rent revenue could be used to finance new projects with smaller loan requirements.

Where will SSHD funding come from?

The SSHD would be eligible to receive city, state, and federal funds, as well as private funds. Already there are signals that the state is dedicating extra funds to increase housing supply: Inslee’s latest budget includes $4B for housing over the next six years and a currently $840M renewal to Seattle’s Housing Levy is scheduled for the November 2023 ballot.

If passed, the program would require an estimated $750k from the City for start-up administrative costs. It will also need to raise monies for its first development projects in the future. This will certainly create some tough decisions on how to divide limited public budgets. But let’s not forget what we’re buying with these costs: we’re buying the opportunity to try a proven solution to affordable housing. And let’s not put the cart before the horse: this is just the cost of testing if the idea works. If it doesn’t work, then we can stop investing in it with the clear conscience of experience; if it works as well as or better than our current interventions, then the investment will make a lot more sense. Finally, let’s remember that the size of the resource pie is not fixed; we can find new ways to raise public revenues. In fact, I think that quantum leaps in spending will ultimately be required to solve the housing supply crisis as quickly as we can.

Are there any other examples of social housing?

The Montgomery County social housing model is based on those that have been functioning for decades in other countries, notably Vienna, Singapore, and Finland.

Iconic public courtyards in one of Vienna’s Gemeindebauten; from Politico

Iconic public courtyards in one of Vienna’s Gemeindebauten; from Politico

Most Singaporeans (78.7% in 2020) live in social housing, and there is a strong market to renovate and take care of the dwellings; from Bloomberg

Most Singaporeans (78.7% in 2020) live in social housing, and there is a strong market to renovate and take care of the dwellings; from Bloomberg

Heka, the public developer of Finland, sets aggressive building requirements for its developments to ensure energy efficiency; from helen.fi

Yes, these are all social housing developments, and in Vienna and Singapore, more than half of all residents live in social housing. In these world-class cities, which have populations of more than 1 million, housing is more like a public good, supported by the government as a kind of mutual insurance to keep residents, and to keep them healthy and productive.

Seattle’s government is planning to reach the 1 million resident milestone within the next 20 years and has half the area of Vienna to work with (160.1 vs 83.78 square miles). Already there isn’t enough housing for everyone who wants to live here; I believe that the private market is not growing fast enough and that government needs to get involved to fill in the gaps. And I think it’s a sound investment: with more productive (housed) people come more businesses, more ideas, more culture, and more tax revenue. We cannot stop people from wanting to live here, so we might as well help them rather than let them struggle. Which brings me to the next point.

Who can live in social housing and how much will it cost them?

The Times article continues,

“The theory is that people would be willing to pay above market rates to subsidize the lower rents of their neighbors in the same building”

This is a very misleading statement. As per the I-135 text, a mixture of rent levels, determined by income, would be required in SSHD developments:

To the extent possible, all developments MUST contain housing units that accommodate a mix of household income ranges, including extremely low-income (0-30% Area Median Income (“AMI”)), very low-income (30-50% AMI), low-income (50-80% AMI), and moderate-income (80-120% AMI), and a mix of household sizes.

Furthermore,

Rental rates MUST be dedicated to permanent affordability and set based on the amount needed for operations, maintenance, and loan service on the building or development containing the unit.

Finally,

The Public Developer should limit rent to no more than 30% of income.

In other words, rental rates are determined by tenant income and building maintenance requirements, not the market, and capped at 30% of that income. While tenants making 120% AMI would pay relatively higher rent than other tenants, it would be no more than 30% of their total income. Market-rate rent is already more than 30% for about half of all renters. The Seattle Times reported that as of last August, 4 of 10 renters in the Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue area were spending more than 30% of their income on rent, and 1 in 5 were spending over 50%.

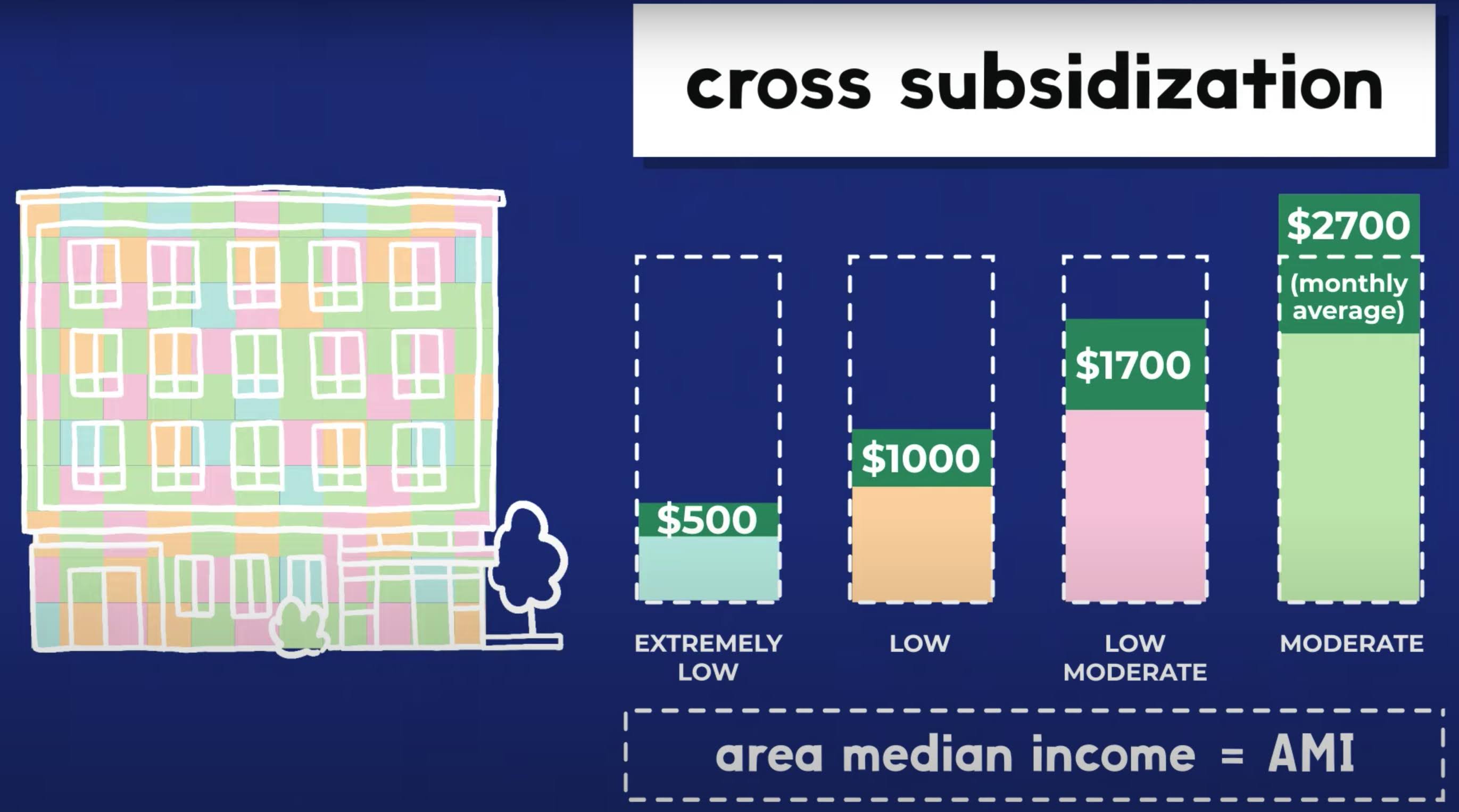

Infographic showing how rent is capped at 30% for different income classes, and how higher rents would cross-subsidize lower rents to meet maintenance costs. From youtube

Infographic showing how rent is capped at 30% for different income classes, and how higher rents would cross-subsidize lower rents to meet maintenance costs. From youtube

Who makes 0-120% AMI?

Most people. In statistics, the median is the middle-valued sample, meaning that anything below 100% AMI is half the total dataset and anything above 100% is the rest of the dataset. Therefore most people in Seattle would be eligible for this housing.

As of this writing, 120% AMI is $105,000 per year per household in Seattle. People making up to that income are not only those in real poverty but also includes teachers, construction workers, childcare providers, and transit operators; people who make the city function and whose professional value is often not fully reflected in their common salary ranges, in my opinion. This kind of housing offers protection for these valuable community members, and the initiative has numerous endorsements from their unions.

I believe that there are significant social benefits to this kind of arrangement as well. Developments that target tenants of the same income class and with identical floorplans create community isolation: only the wealthy are able to afford living near the wealthy, and more importantly poor people are forced to live in underresourced and stigmatized areas. This option also dovetails well with the popular proposed Alternative 6 development strategy, which would promote multifamily housing all over the city.

Another problem with developments that target a specific class and family size is their inflexibility to accommodate changes in their tenants’ lives. Section 8 vouchers, for example, have strict income limits for eligibility. Tenants that earn a raise may have to make the difficult decision between accepting that raise and moving. SSHD housing would simply adjust the rent based on the new income level; evictions based on changes to household income are banned. The mixture of floorplans also helps retain families as they grow and shrink over the years.

What’s the difference between this program and others that already exist?

The primary opposition to I-135 comes from the Housing Development Consortium (HDC), and their comment is echoed in the Times opinion:

“We do not need another government entity to build housing when there are already insufficient resources to fund existing entities.”

It’s tempting to take the HDC’s opinion at face value, after all, they’re called the Housing Development Consortium; however, it’s important to know that the HDC is comprised of those same insufficiently resourced entities, mostly non-profit developers. In other words, they’re looking out for themselves and that totally makes sense. But I do not believe that the SSHD is just “another government entity;” it would provide permanent and quality housing for low and middle income residents. This is a need we need to address in addition to the important and necessary work of the HDC. Next I’ll highlight a few other important differences.

The first misconception one might draw from HDC’s statement is that SSHD would be going after all the same funding sources as the existing non-profit developers. In fact, SSHD would be ineligible to apply for federal programs such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and Section 8 vouchers that many non-profit developers use. There would be some competition for other monies, but the SSHD’s ability to issue bonds makes its business model fundamentally different from the others. If SSHD is successful, then much of its costs could be financed by traditional debt capital sources, such as banks, and subsidized by its revenues; in other words, housing that it provides will come at the cost of much fewer taxpayer dollars. SSHD also has opportunities to greatly reduce its capital costs by using public lands, rather than having to buy land off the private market.

Another important difference is that SSHD homes need to be built to high efficiency and materials sourcing standards. From the official initiative text:

New developments MUST meet green building and Passive House Standards.

Passive House uses design to minimize the need for space heating and cooling regardless of changes in the outdoor environment. Recent heatwaves in the Pacific Northwest show the need for resilience to extreme weather in new construction. At the same time, the state’s emissions goals require that resilience to come with no impact to emissions. We can’t meet our goals by putting air conditioners (even heat pumps!) in every home and running them full blast every summer and winter.

While it will raise initial building costs, building to these standards will result in higher quality and longer-lived homes. They will have lower maintenance burdens over their lifetimes and lower energy costs for owners and tenants. They will be more comfortable to live in. I suspect that residents will take better care of them than low-quality and uncomfortable living spaces. We need to start increasing our stock of these homes as soon as possible, and this momentum will make it easier for private developers to build them as well.

Finally, the housing built by SSHD will remain in the public domain forever. The developments can’t eventually be sold to private owners, which can happen at the minimum only after 15 years for some public housing programs. That’s less than a single generation of housing! This permanent stock will prevent public investments from losing public value. What was intended for public use will remain in public use.

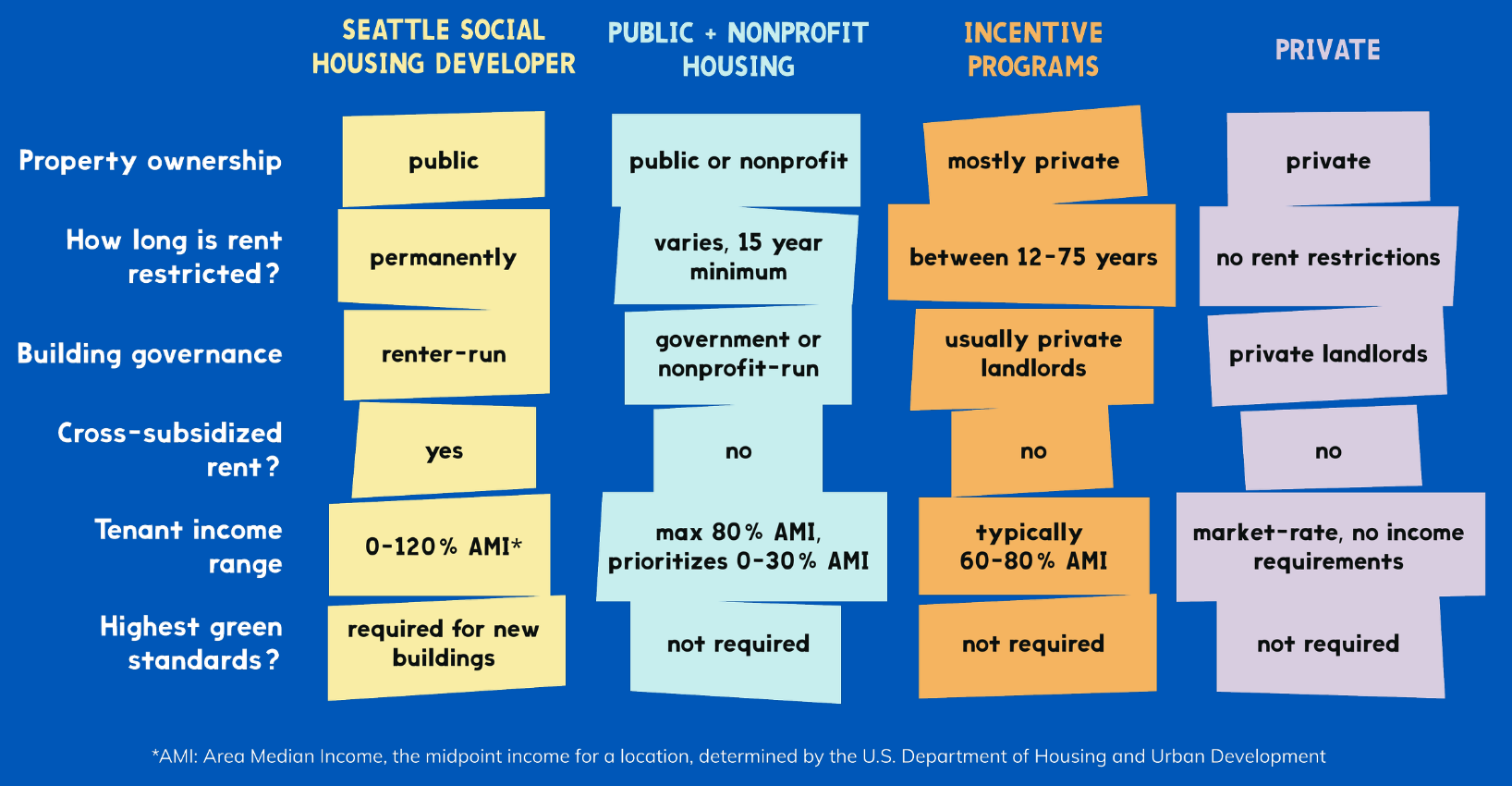

Comparison of how long rent is restricted between housing types, from House Our Neighbors

Comparison of how long rent is restricted between housing types, from House Our Neighbors

Conclusion, and will this reduce homelessness?

I believe that more housing supply will reduce homelessness. Housing is needed for all income levels; obviously, for those making less than 30% AMI, but also for those in the 30-80% range. Even up to the 100% range. The people in these income ranges are in the low to middle classes, already rent-burdened, and are all at risk to suffer financial crises, like medical emergencies, layoffs, and thefts, that could make them homeless overnight.

I believe that creating a supply of housing that is permanently affordable offers a safety buffer for these residents, as well as those exiting homelessness, against market forces. But it will take some time to develop this supply with I-135, as it is a long-term program that seeks to create permanent housing solutions. Rejecting I-135 for the sake of other programs that seek to create housing for the lowest income brackets I think is a false choice; we need to try all of these approaches.

Therefore I think that this vote is really a referendum on whether we are ready to put our money and our political will where our mouths are when we say that we want to solve the housing shortage problem. Are we ready to try good ideas that have been successful elsewhere? Are we ready to say “and” rather than “or”? Are we ready to continue to figure out the unknowns to make this work, rather than clinging to known but incremental outcomes? Are we ready to meet our ambitious equity, sustainability, and growth goals? I think so, so that’s why I’m voting YES on I-135.